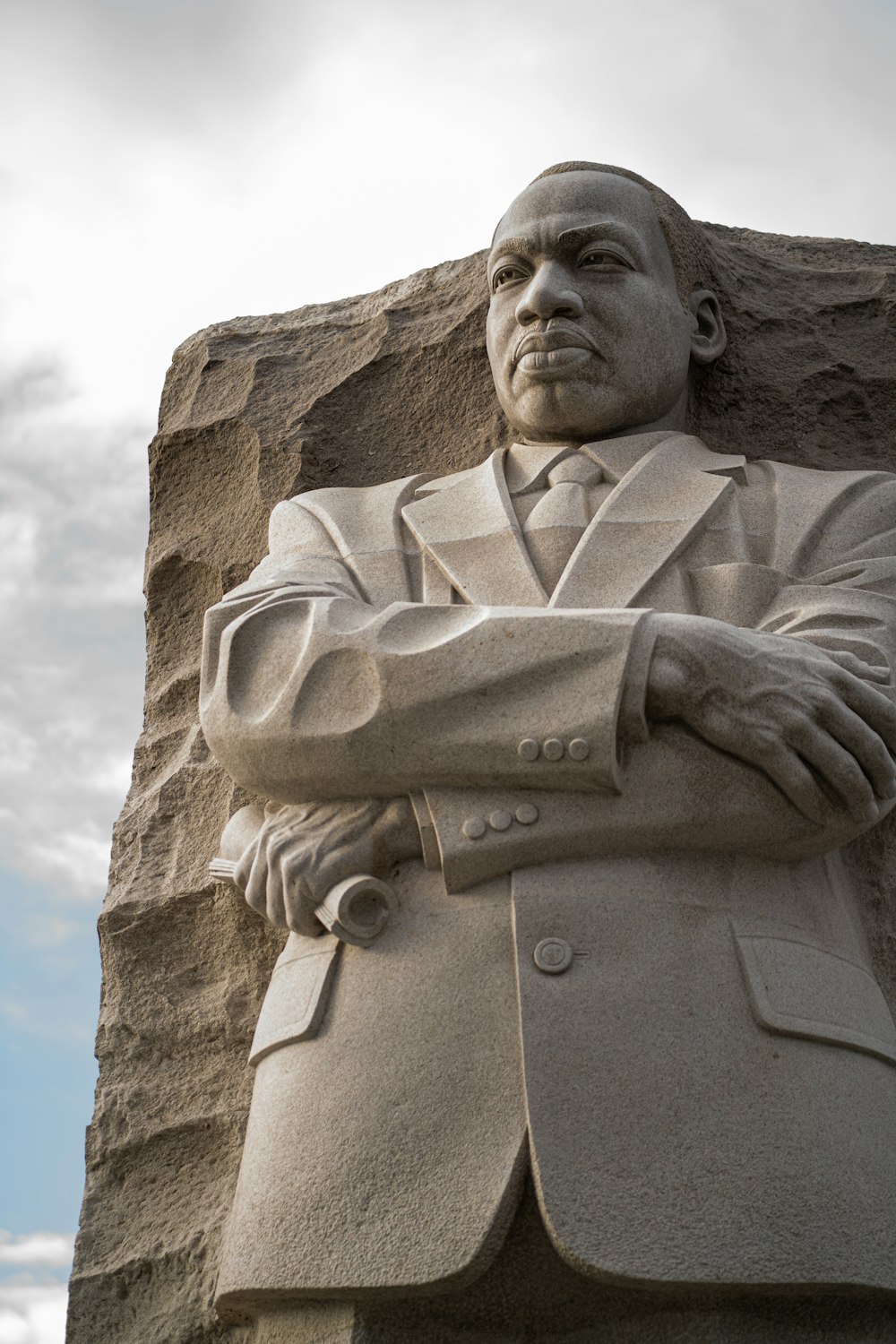

Every January, we celebrate a sanitized version of Martin Luther King Jr.—a dreamer with a timeless speech, a gentle hero of a bygone era. This comfortable iconography misses the man entirely. The real King was not just a visionary but a **strategic disruptor**, a man whose power lay in creating what he called "creative tension" to force a nation to confront its own hypocrisy. To remember him only for his dream is to forget the costly, deliberate, and often unpopular work that made the dream audible.

The Architect of "Creative Trouble"

King did not stumble into leadership. He was a PhD in systematic theology who chose nonviolence not as a passive stance, but as a **weapon of the disciplined**. After Rosa Parks' arrest, the Montgomery Bus Boycott wasn't a spontaneous protest; it was a meticulously planned economic and logistical campaign lasting over a year. King's genius was understanding that segregation's weakness was its dependency on Black compliance and economic participation. The boycott weaponized collective withdrawal.

His strategy was never to ask politely for change. It was to **stage a moral crisis so public and so undeniable that the status quo became untenable**. He didn't go to Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963 because it was the most racist city—he went because he knew its police commissioner, Bull Connor, would react with televised brutality. The images of children being attacked by dogs and fire hoses were not a public relations failure for King; they were the brutal, intended result that finally cracked the conscience of white moderates across the nation.

The "Letter from Birmingham Jail": A Rebuke to the Comfortable

While jailed during that campaign, King wrote his most profound text, not for his opponents, but for his **critics on the sidelines**: white clergy who urged "patience" and "order." The "Letter from Birmingham Jail" is a masterclass in moral argument.

"Frankly, I have yet to engage in a direct action campaign that was 'well timed' in the view of those who have not suffered unduly from the disease of segregation. For years now I have heard the word 'Wait!'... This 'Wait' has almost always meant 'Never.'"

Here, King identified the greatest barrier to justice: not the hooded racist, but the "white moderate" who prefers a negative peace (the absence of tension) to a positive peace (the presence of justice). This letter reframed the entire movement: the disruptors were not the problem; the true threat was the comfort of those who valued order over equality.

The Radical Evolution They Forget to Mention

By 1965, after the victories of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts, King knew legal desegregation was not enough. He pivoted to a far more radical and unpopular fight: **economic justice**. He launched the Poor People's Campaign, demanding guaranteed income and attacking the "triple evils" of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism.

He opposed the Vietnam War with searing moral clarity, alienating President Lyndon B. Johnson and much of the mainstream media that had once praised him. "A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death," he declared. This King—the anti-war, democratic socialist critic of capitalism—is often left out of the holiday tributes, yet it was the logical culmination of his belief that an "inequality of opportunity" was the deeper, more resilient enemy.

The Dream as a Measure of Our Failure

The "I Have a Dream" speech is not a feel-good anthem. It is a **devastating indictment**. King describes the promise of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution as a "bad check" returned to Black Americans marked "insufficient funds." The dream is the vision of what cashing that check would look like.

To celebrate the poetry of the dream while ignoring the systemic economic and policy reforms he died fighting for is to hollow out his legacy. The dream was a destination; his life was the grueling, dangerous, and politically fraught journey to get there—a journey we have not completed.

The Unfinished Work

King was assassinated in Memphis while supporting underpaid Black sanitation workers. His last public speech, the eerily prophetic "I've Been to the Mountaintop," was not about a dream fulfilled, but about the ongoing struggle. "We've got some difficult days ahead," he said. "But it really doesn't matter with me now, because I've been to the mountaintop... And I've seen the promised land."

He saw it, but he didn't get there. His legacy is not a completed monument but an **unfinished blueprint**. The true way to honor him is not with quotes on a poster, but by asking the uncomfortable questions he asked: Who is still being handed a bad check? Where does our comfort depend on the inequality of others? And what "creative tension" must we responsibly generate today to build the justice he was still fighting for on his last day?

The icon comforts us. The real man challenges us. The choice of which one we remember reveals how seriously we take the work he left behind.